|

|

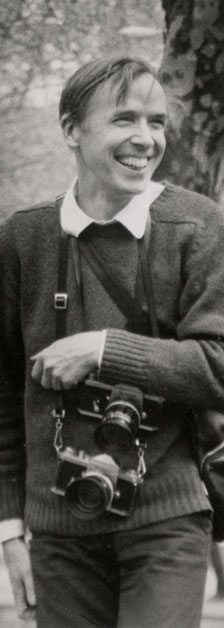

ABOUT BILL William John "Bill" Cunningham Jr. (March 13, 1929 – June 25, 2016) was an American fashion photographer for The New York Times, known for his candid and street photography. A Harvard University dropout, he first became known as a designer of women's hats before moving on to writing about fashion for Women's Wear Daily and the Chicago Tribune. He began taking candid photographs on the the streets of New York City, and his work came to the attention of The New York Times with a 1978 capture of Greta Garbo in an unguarded moment. Early life and education Career Cunningham photographed people and the passing scene in the streets of Manhattan, often at the corner Fifth Avenue and 57th Street. As he worked, his focus was on clothing as personal expression. He did not photograph people in the manner of paparazzi, preferring genuine personal style to celebrity. He once explained why he was not joining a group of photographers who swarmed around Catherine Deneuve: "But she isn't wearing anything interesting." Late in life he explained: "I am not fond of photographing women who borrow dresses. I prefer parties where women spend their own money and wear their own dresses.... When you spend your own money, you make a different choice." Instead, wrote Hilton Als in The New Yorker, "He loved 'the kids,' he said, who wore their souls on sleeves he had never seen before, or in quite that way." He was uninterested in those who showcased clothing they had not chosen themselves, which they modeled on the red carpet at celebrity events. Most of his pictures, he said, were never published. His fashion philosophy was populist and democratic: Fashion is as vital and as interesting today as ever. I know what people with a more formal attitude mean when they say they're horrified by what they see on the street. But fashion is doing its job. It's mirroring exactly our times. He wrote fashion criticism and published photo essays in Details, beginning with six pages in its first issue in March 1985 and sometimes filling forty pages. He was part owner of the magazine for a time as well. His work there included an illustrated essay that showed similarities between the work of Isaac Mizrahi and earlier Geoffrey Beene designs, which Mizrahi called "unbelievably unfair and arbitrary". In any essay in Details in 1989, he was the first to apply the word "deconstructionism" to fashion. His personal philosophy was: "You see, if you don't take money, they can't tell you what to do, kid." He sometimes said it another way: "Money is the cheapest thing. Liberty is the most expensive." He declined all gifts from those he photographed, even offers of food and drink at gala parties. He said: "I just try to play a straight game, and in New York that's very... almost impossible. To be honest and straight in New York, that's like Don Quixote fighting windmills." Though he contributed to the New York Times regularly beginning in the 1970s, he did not become an employee until 1994, when he decided he needed to have health insurance coverage after being hit by a truck while biking. Most of his pictures were never sold or published. He said: "I'm really doing this for myself. I'm stealing people's shadows, so I don't feel as guilty when I don't sell them." Designer Oscar de la Renta said: "More than anyone else in the city, he has the whole visual history of the last 40 or 50 years of New York. It's the total scope of fashion in the life of New York."[14] He made a career taking unexpected photographs of everyday people, socialites and fashion personalities, many of whom valued his company. According to David Rockefeller, Brooke Astor asked that Cunningham attend her 100th birthday party, the only member of the media invited. He cultivated his own fashion signature, dressing in his personal uniform that included black sneakers and a blue work man's jacket. His only accessory was a camera. He travelled Manhattan by bicycle, repeatedly replacing those that were stolen or damaged in accidents. He praised the city's bike sharing program when it launched in 2013: "There are bikes everywhere and it's perfect for the New Yorkers who have always been totally impatient. What I love, is to see them all on wheels, on their way to work in the morning in their business suits, the women in their office clothes ... It has a very humorous and a very practical effect for New Yorkers ... I mean, it's wonderful." After breaking a kneecap in a biking accident in 2015, he wore a cast and used a cane to cover a Mostly Mozart Festival gala.[34] For eight years beginning in 1968, Cunningham built a collection of vintage fashions and photographed Editta Sherman in vintage costumes using significant Manhattan buildings of the same period as the backdrop. Years later he explained that "We would collect all these wonderful dresses in thrift shops and at street fairs. There is a picture of two 1860 taffeta dresses, pre–Civil War–we paid $20 apiece. No one wanted this stuff. A Courrèges I think was $2. The kids were into mixing up hippie stuff, and I was just crazed for all the high fashion." They project grew to 1,800 locations and 500 outfits. A selection of these photos were displayed in 1977 in an exhibit at the Fashion Institute of Technology called the "Facades Project". In 1978, he published Facades, a collection of 128 of these photographs. Awards and Honors Cunningham died age 87 in New York City on June 25, 2016, after being hospitalized for a stroke. His death was widely reported in both the fashion and the general press. [Bio courtesy of Wikipedia] See Bill’s On The Street slideshow on The New York Times See a New York Magazine slideshow of Bill’s amazing work as a milliner in the 1950s |